From Cortado to Consumer

It's not just coffee. It's an artifact of modern work culture and consumerism.

“Cortado, full milk, please.” I used to be an Americano guy, but for the past 6 months, I’ve been addicted to the not-quite-a-macchiato-but-not-a-Latte-either drink1. But like any committed consumer, I’ll soon get tired of cortados and switch to another type.

Every day, 2 billion people partake in their daily coffee ritual, mainly to stay awake. Unwittingly, we are all participants in a long consumer history that connects us to groups as diverse as 9th-century Ethiopian shepherds, revolutionary Parisian philosophers, or even Ariana Grande fans. Whether we prefer coffees dark and bitter or sweet and barely caffeinated, our evolving coffee preferences are key to modern work culture and consumerism.

Brief History: Kaldi and the Frisking Goats

“...the goats were running about, butting one another, dancing on their hind legs, and bleating excitedly. In winded wonder, the boy stood gaping at them. They must be bewitched, he thought….

First, he chewed on a few leaves. They tasted bitter. As he masticated them, however, he experienced a slow tingle, moving from his tongue down into his gut, and expanding to his entire body…Soon, according to legend, Kaldi was frisking with his goats. Poetry and song spilled out of him. He felt that he would never be tired again.”

In the 15th century, most of the world had not tasted the wonders of coffee. The only people enjoying the magical bean were Ethiopian monks, who had been tipped off by a goatherder-and-poet named Kaldi.

By the 16th century, coffee had spread throughout the Arabian Peninsula and the broader Ottoman Empire. Around 1573, the Venetians started importing it into Europe. By the 17th century, coffee houses mushroomed in Paris, London, and Vienna —and Europeans started frisking too.

The Coffeehouse: From Luxury to Mass Consumption

Like all luxury goods, coffee—along with cocoa, tobacco, sugar, and tea—was consumed only by the elites who could afford it. But as trade with the Americas exploded in the 18th century, the supply of coffee increased and prices went down. Once a privilege of only Europe's wealthiest inhabitants, coffee was now within reach of the middle and even the lower classes

“Consumption [of coffee] has tripled in France; there is no bourgeois household…who does not breakfast on coffee with milk in the morning. In public markets and in certain streets and alleys in the capital, women have set themselves up selling what they call café au lait to the populace” — 18 century Frenchmen quote (cited in Zwart and Zanden, p. 249).2

The most well-known result of this affordability was the rise of coffeehouses— spaces in which caffeinated minds socialized, debated, and conducted business.

By the 18th century, Paris alone had around 700 coffeehouses. One of the most famous ones, Café de Procope, established in 1686, was where Voltaire, Rousseau, and later Robespierre and Marat, sipped their coffee and philosophized about their revolutionary ideas. The French Revolution and Enlightenment brewed in the minds of over-caffeinated French thinkers.

In England, coffeehouses, known as “penny universities,” became influential hubs where thinkers from all social strata could freely share their ideas. So freely that King Charles II tried to ban penny universities in 1675. Frisking coffee addicts revolted and the ban lasted only 11 days.

“coffee-houses... have produced very evil and dangerous effects; …divers false, malicious, and scandalous reports are devised and spread abroad, to the defamation of His Majesty's Government and to the disturbance of the peace and quiet of the realm..." — King Charles II, Enemy of Coffeehouses for 11 days.

Like any revolutionary consumer product, coffee started as a luxury afforded only by the elites. Then the masses craved it. Demand increased, supply increased, and prices went down. Coffee became a household staple and coffeehouses became powerful hubs of revolutionary thought. So powerful that not even the King could stop them.

The Industrious Revolution: Wake Up, Want More, Work Harder

As they were chugging coffee, the Euros were also craving luxury goods like Chinese porcelains, Asian cloth, and more sugar, tea, and tobacco. This 'consumer revolution' led to more trade, more shops, more specialization, more jobs, and economic growth.

People worked harder to afford these new exotic luxuries. A tradesman from the time observed, “[the desire for the new luxuries] disposes people to work, when nothing else will incline them to it; for did men content themselves with bare necessities, we should have a pure world”(Zwart and Zanden, p. 252). Historian Jan de Vries named this time "the industrious revolution."3 a demand-side revolution that preceded the Industrial Revolution.

In the 15th century, English farm laborers worked 165 days per year; by the late 18th century the number increased to 260 days. Not only did men work longer, but children and women also diverted time from domestic work to market work.

“I drink coffee, So I can work longer, So I can earn more, So I can drink more coffee” — Thorstein Veblen, "The Theory of the Leisure Class," 18994

One theory posits that working hours increased because real wages declined in the latter half of the 18th century, pressuring workers to work longer to maintain their standard of living.

However, two researchers in 2011 employed a variety of quantitative techniques to challenge this notion and showed that the import of coffee, sugar, and tea had a significant positive impact on the standard of living of early modern Europeans. Access to a broader array of goods, they argued, significantly enhanced people's lives: “the introduction of caffeinated hot beverages and sugar [in Britain] contributed substantially to the welfare of the first industrialized country”(Hersh and Voth, p. 35)5.

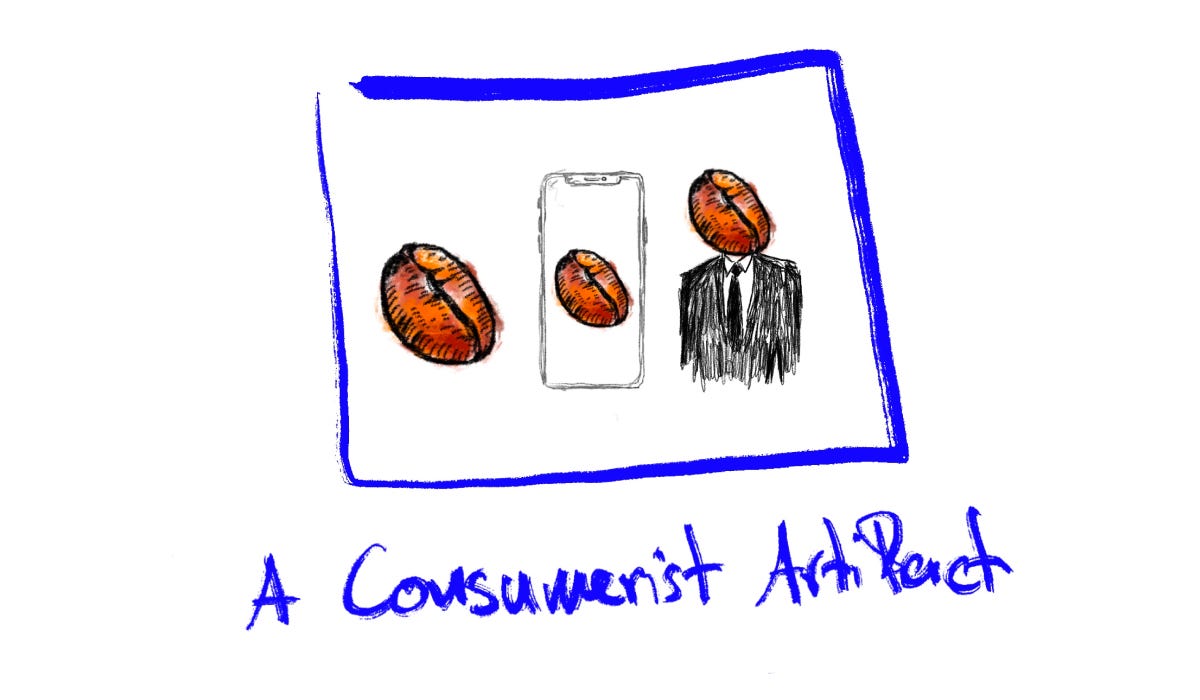

An Artifact of Modern Consumerism

Today, coffee remains an ideal artifact of consumer culture, always selling and reinventing itself. First-wave culture, second-wave, third-wave, fourth-wave. Spiced Pumpkin Toasted White Chocolate Mocha. Ariana Grande Frappuccino. Bulletproof coffee. Monkey poop coffee.

Starbucks, the iconic coffee chain, is worth $90 billion (that’s more than Shopify, Palantir, and Stripe). Blue Bottle was valued at $700 million when Nestle acquired 68% of it. Blank Street raised more than $100 million. Like any powerful consumer product, coffee doesn’t satisfy only our biological needs but our social and status needs too… sit at Ralph’s Coffee in NYC for an anthropological field observation of this phenomenon.

Coffee made Ethiopian goats frisk, inspired philosophers to revolt, and drove 18th-century men to work harder and consume more. It has always been and remains one of the most powerful consumer products. Whether you start your morning with a cortado or an Ariana Grande Frappuccino, you’re continuing a legacy that underpins modern work culture and consumerism. Now that you know this history, I hope your morning coffee tastes even better. It certainly does for me.

I recently learned Jeremy Strong is a cortado man as well.

The Industrial Revolution and the Industrious Revolution, Jan De Vries, 1994.

Not real, fake news.

Sweet Diversity: Colonial Goods and the Welfare Gains from Trade after 1492, Jonathan Hersh and Hans-Joachim Voth, 2011.